“Ela,” the man shouted from his car window, and waved his arm with force.

“Ela,” the man shouted from his car window, and waved his arm with force.

“He wants us to follow him,” Nick, explained.

“I know but why is he angry at…” I stopped mid-sentence, remembering: everyone in Greece acted in fits of passion. The previous day, as part of a trip from London, I had walked past two Athenians who I thought were in the middle of an argument but they were just complimenting one another’s dogs.

Yiannis directed us to to his vineyard and hacked away at bunches with free abandon. We couldn’t fill the bags he had given us fast enough, the ripe and ready grapes piling in our hands when we couldn’t fit in any more. Back in the village, a woman welcomed us into a guest house for the night, the room as no cost to the people she was excited to host. That next morning, another couple had been asked to drive us thirty minutes up a steep dirt track. We parked by the many cars that had beaten not only us but the break of dawn, and from where we would continue the annual pilgrimage on foot. We had never met these people yet the villagers of Kastorio welcomed us like we were old friends.

Nick had a link; his grandmother had once lived within this small community at the foothills of the Taygetus Mountains in the Peloponnese. She had died over thirty years ago, the house was dilapidated and Nick’s boyhood summer visits were distant memories. It didn’t matter to anyone we met; they knew the name, they had stories, and Yiannis even showed us the barber chair that Nick’s great grandfather had brought over from America in 1926 and that he was now restoring. As for me, I was the only non-Greek that morning but everyone was too busy watching their step on the precarious climb to pay any attention.

Our driver had been baptised sixty years ago at the Ai Yiannis O Nisteftis church atop the mountain and sped off on foot, carrying four loaves of bread over his shoulder, and beating us up there by twenty minutes. This was the yearly climb to the church of St John the Faster, now only open on the 29th August. Mules passed with ease on the rocky path as we climbed in time with the sun. An hour later we were met at the summit with a view of southern Greece. We stopped outside a small stone church beside the steep cliff face, large enough to hold ten people whilst another eighty stood nearby and listened to the chanting on loudspeakers. Soon, an Orthodox Priest paraded a loaf of bread through the crowd and blessed it with a kiss, whilst locals broke up more loaves into chunks and distributed them. Each slice was different: one a bitter sour-dough, one more flavoured with nutmeg, another with mastic resin.

By mid-morning the sun was already at full force and it was time to head back. Halfway down, we pulled over to a simple house built within the tree-lined mountainside. More people we had never met welcomed us to their table and we shared home-made apple pie and wine. Nearby was a marble fountain with an outpouring of fresh water and from there a trail to the next house farther along the footpath that continued to the valley beneath, connecting the summer residences along the way. Those owners called us to join them for olives, sweet breadsticks and raki. Not long after, we heard a shout from above. “Go to the next house down,” our driver said. “I’ll meet you there for lunch.”

There, for yet another meal, we sat at a trellis table overlooking a glorious panorama of the Greek countryside. Behind us, a kitchen had been built along an outcrop, open to the elements, and from where we were served lentil soup. Home-grown tomatoes and cucumbers accompanied this and were a gastronomic affair, each bite worthy of an additional Michelin star.

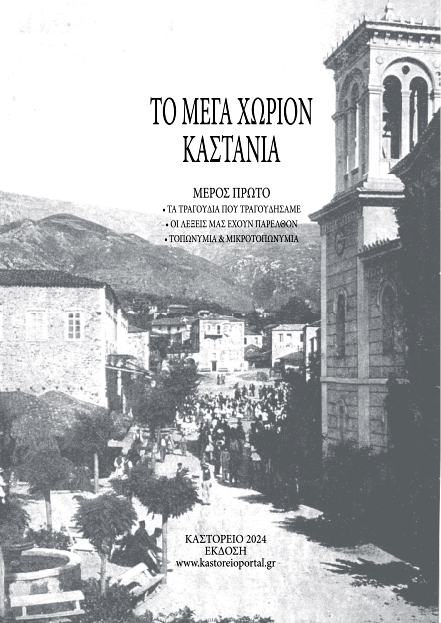

Woozy-headed – and not from the altitude – and with no stomach space left, we refused another meal with abundant apologies. The couple stopped after a few turns in the road to show us a view of the village, as sleepy as anywhere I had visited. The few restaurants and cafes on the sole arcade offered plenty of tables but with no tourists to fill them. The population grew in the summer but the year-round residents had depleted to a few hundred. All around were chestnut trees that gave the original name of Kastania to the village but in 1921 the Greek State wanted to erase Ottoman and Slavic references and renamed the place Kastorio for the Kastor River that ran through it. (Some locals also told us the name paid homage to the brothers Castor and Pollux.) We said our goodbyes and jumped at the offer to return in November for the olive harvest and first pressing of olive oil.

As we drove away, and in between munches on grapes despite the fact I was stuffed, I asked Nick how everyone could be so hospitable when we had little to offer. He reminded me I had given something; on the way down the mountain after the ceremony I had carried a heavy microphone stand. It was the least I could do but my offer had not gone unnoticed.

I smiled ahead to the olive oil and the reunion with people I looked forward to seeing once more. Kastorio was lost to the past, perhaps, but it was a place that could feel like home in the future. My own pilgrimage had not just been to St John the Faster but one of someday moving across the continent. I was the Englishman who went up a hill but came down a Greek.